• The volume examines the legacy of the Treaty of Tlatelolco and the new challenges facing nuclear disarmament, from cybersecurity to the growing crisis of deterrence.

By Guillermo Ayala Alanis

Mexico City (INPS Japan) – At a time when nuclear deterrence appears to be re-emerging as a central pillar of global power, Latin America and the Caribbean continue to press a counter-argument: that genuine security is best achieved without nuclear weapons.|SPANISH|JAPANESE|

A 80 años de la era nuclear: ¿Dónde estamos y a dónde vamos? Una mirada desde México y América Latina (80 Years into the Nuclear Age: Where Are We and Where Are We Headed? A View from Mexico and Latin America) reviews the progress, risks, and enduring dilemmas of nuclear disarmament from the perspective of the world’s first Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone.

The book is coordinated by María Antonieta Jáquez Huacuja, Coordinator for Disarmament, Non-Proliferation, and Arms Control at Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Abelardo Rodríguez Sumano, professor and researcher at Universidad Iberoamericana. They emphasize that the publication updates the theoretical and conceptual debate on nuclear weapons while addressing diplomacy, multilateralism, and emerging risks.

These include evolving threats linked to nuclear terrorism, artificial intelligence, and cybersecurity—particularly the dangers posed by hacking and the manipulation of information related to nuclear systems.

When Not Having Nuclear Weapons Creates Greater Security: Latin America’s Gamble

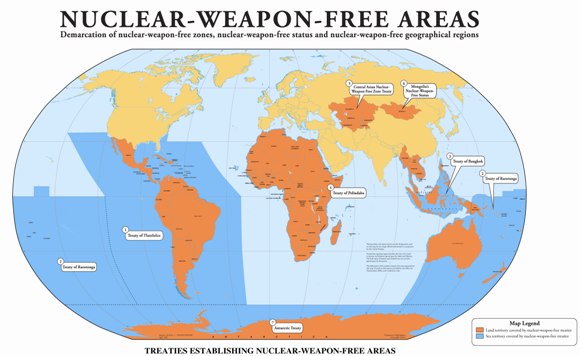

The war in Ukraine, recent U.S. military actions in Venezuela, and threats directed at Greenland all point to a broader realignment of the international order. Yet even as major powers rethink their security doctrines, Latin America and the Caribbean remain firmly committed to the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and to strengthening Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones (NWFZs).

In an interview with INPS Japan, Dr. Rodríguez Sumano argued that the absence of nuclear weapons is the strongest security guarantee for Latin American and Caribbean states at a time when the policies of major military powers—including China, Russia, and the United States—are under reassessment.

“Not having nuclear weapons does not generate additional pressure for the United States to intervene in countries it may consider adversaries or contrary to its interests,” he said. “That equation significantly reduces pressure, confrontation, and even the likelihood of intervention or political overthrow of any regime Washington might eventually view as a threat.”

Rodríguez Sumano also highlighted the enduring importance of the Treaty of Tlatelolco, which will mark its 59th anniversary on February 14. By banning the manufacture and dissemination of nuclear weapons across the 33 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, the treaty laid the foundations for a regional system of peace and security.

He noted that the treaty—and the creation of the Latin American and Caribbean Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone—served as a model for the creation of nuclear-weapon-free zones in other parts of the world, with similar frameworks spreading to four additional regions—the South Pacific (Treaty of Rarotonga), Southeast Asia (Treaty of Bangkok), Africa (Treaty of Pelindaba), and Central Asia (Treaty of Semipalatinsk). Together, these zones now bind 117 states, covering more than 50 percent of the Earth’s surface, to legally binding commitments against nuclear weapons proliferation.

The region’s choice is all the more significant given its history. In 1962, Latin America and the Caribbean could have become the site of an unprecedented nuclear confrontation during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the United States and the Soviet Union stood on the brink of war.

Deterrence as a Tool of Hegemony and Survival

Despite this experience, Rodríguez Sumano cautioned that nuclear-armed states continue to rely on deterrence as a means of preserving both hegemony and survival.

“This is how the United States thinks, and Moscow thinks in much the same way,” he said. “They believe sovereignty is guaranteed to the extent that survival within the international system can be ensured—and from that perspective, nuclear weapons are seen as the means to achieve that survival.”

He stressed that the behavior of major powers changes markedly when dealing with countries that possess nuclear capabilities.

“They behave differently,” he said. “Russia, for example, acts differently toward China or North Korea. The United States, too, has refrained from direct military action against North Korea. Nuclear capability fundamentally alters strategic calculations.”

Rodríguez Sumano also pointed to a broader reshaping of the Atlantic order. Europe, he argued, now faces a dual challenge: responding to Russia’s expansionist ambitions while also managing new forms of pressure, including military threats linked to the possible annexation or acquisition of Greenland.

New Risks Driven by Technological Change

One of the book’s key strengths is its direct focus on emerging risks that traditional approaches to arms control are increasingly ill-equipped to address. The spread of cyberattacks, artificial intelligence (AI), and information warfare is making the systems used to manage nuclear weapons far more complex—and potentially more vulnerable.

The book points, for example, to the risk of unauthorized intrusions into the systems responsible for nuclear command and control, as well as the possibility that early-warning data used to detect missile launches could be manipulated. It also warns that if AI-assisted decision-making malfunctions, it could lead to dangerous misjudgments. Such scenarios could introduce new sources of instability into an already fragile framework of nuclear deterrence.

The editors argue that these challenges are not distant, hypothetical threats but practical problems the world is already beginning to face. For that reason, they call for updated rules suited to today’s realities, alongside renewed efforts to strengthen cross-border cooperation.

In this respect, the book suggests that Latin America’s experience—rooted in diplomacy, verification mechanisms, and international agreements—offers lessons that remain relevant well beyond the region.

A Freely Accessible Book with Global Reach

In addition to its print edition, A 80 años de la era nuclear is available for free download from the website of the Mexican Association of International Studies (AMEI):https://amei.mx/biblioteca-virtual/80-era-nuclear/libro-completo/

An English translation is currently in preparation, and efforts are underway to support a Japanese edition as well.

The volume includes contributions from prominent international figures, among them Rafael Mariano Grossi, Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency; Jans Fromow Guerra, a member of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN); Martha Mariana Mendoza Basulto, International Relations Officer at OPANAL; and Maritza Chan Valverde, Costa Rica’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.

What the contributors’ analyses collectively underscore is that even in an era of renewed nuclear risk, the disarmament path pursued by Latin America and the Caribbean is far from outdated. Rather, it represents an alternative approach to security—one that can function within the realities of international politics.

Eighty years after the dawn of the nuclear age, as the world shows signs of returning to the logic of “deterrence,” the region’s experience once again forces a fundamental question: does security truly have to depend on nuclear weapons?

This article is presented by INPS Japan, in association with Soka Gakkai International, which holds consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), January 2026.

This article is brought to you by INPS Japan in collaboration with Soka Gakkai International, in consultative status with UN ECOSOC.